There’s something inherently intellectual about being a Beyoncé fan. I’m not talking about surface-level admiration—the "she can sing and dance at the same time!" crowd (though, yes, she absolutely can). I’m talking about the real fans. The ones who see the visuals, hear the horns, catch the interludes, track the lineage, and feel the political undercurrent running through every beat. If you know, you know: being a Beyoncé fan is a masterclass in cultural fluency.

She doesn’t just make albums. She curates sonic museums. She doesn't just perform—she archives. And with each new era, she invites us, her fans, to go deeper. To study. To remember. To reclaim.

Blackness, Reclaimed & Reframed

Beyoncé has never been just a pop star. She is a living, breathing cultural institution. And like any good institution, her work tells stories—not just of her own personal growth, but of our shared history. Specifically, of Black history. Of Southern roots. Of queer influence. Of American contradictions. Of legacy.

When Renaissance dropped, it wasn’t just a pivot to house music—it was a reclamation. House music, a genre often commercialized by white artists and misunderstood by the masses, was born in Black queer clubs. It was protest and pleasure. Freedom through frequency. Beyoncé reminded the world of that—not quietly, but boldly. Through production choices, collaborations, references, and above all, intention.

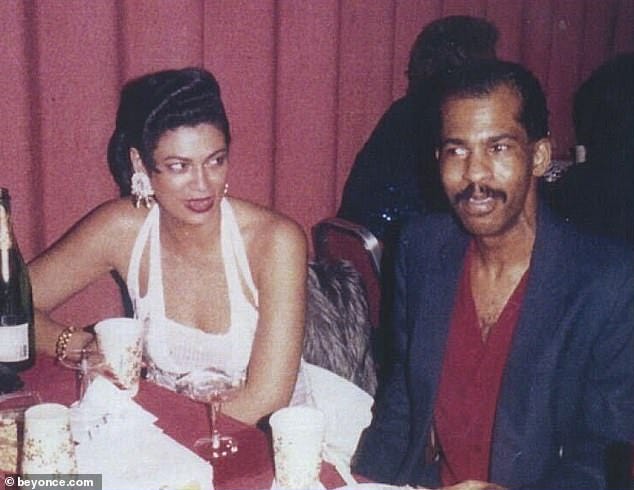

And she said it plainly: this album was for her Uncle Jonny. Her uncle, a Black gay man who introduced her to high fashion and taught her how to twirl, was the pulse of the Renaissance era. The heartbeat behind the glam. That wasn’t just a tribute—it was preservation.

Cowboy Carter: A Southern Gothic Restoration

Now she’s doing it again.

Different genre, same mission: reclamation.

Cowboy Carter is not a country album. It is an excavation. A sonic retelling. A Black woman’s manifesto dressed in cowboy boots and American mythology. Beyoncé’s not interested in asking for permission to enter the genre—she’s here to remind you she never needed it.

As Linda Martell states on the SPAGHETII track herself: “Genres are a funny little concept, aren’t they?”

Country music—like rock, like jazz, like house, like hip-hop—has Black roots. Beyoncé knows this. Her fans know this. But the industry often pretends to forget. So she pulled up to the (country) table with receipts, history, and that voice—and made herself undeniable again.

Cowboy Carter isn’t just about music—it’s about the audacity to belong. To take up space. To remind the world: we were always here.

Cultural Intelligence Is Required

This is what makes Beyoncé fans different. Not better—though, maybe—but definitely different.

Because to love Beyoncé is to study.

To read liner notes.

To research samples.

To ask questions like: “Wait, wasn’t that line a nod to a certain historical moment?”

To watch the visuals and say, “That’s not just aesthetic. That’s coded.”

To know that every outfit, every stage set, every collaborator, every note matters.

Beyoncé demands intellectual engagement. She is both the pop culture and the cultural critique. Both muse and historian. Both celebration and syllabus.

And to really ride with her? You have to listen. Not just hear—listen.

So, What’s the Lesson Here?

If you’ve ever called Beyoncé overrated, you either aren’t listening, or you haven’t done the homework. Period.

Her catalog is Black American history with a beat.

Her visuals are cultural essays dressed in couture.

Her stage performances are dissertations with wind machines.

To be a Beyoncé fan is to be culturally intelligent. To be spiritually aligned. To be emotionally expansive. To care about context. About meaning. About the power of storytelling when told from the margins.

So no, we’re not just stanning a pop star. We’re following a cultural architect through the archives of our own past—and watching her build a new future in real time.

Written by:

Nina Orm